Arabic is a Semitic language spoken by over 420 million people predominantly in countries across the Middle East and North Africa. As one of the world’s most widely spoken languages, Arabic has a long and storied history spanning over 1,500 years. This article will provide an overview of the origins and development of Arabic over the centuries, looking at its beginnings on the Arabian Peninsula, how it spread through trade and Islam to become the common tongue of science and culture during the Islamic Golden Age, its evolution into diverse regional dialects, attempts to standardize it into Modern Standard Arabic, and its trajectory in recent centuries faced with the dominance of global English.

Origins and Early Development

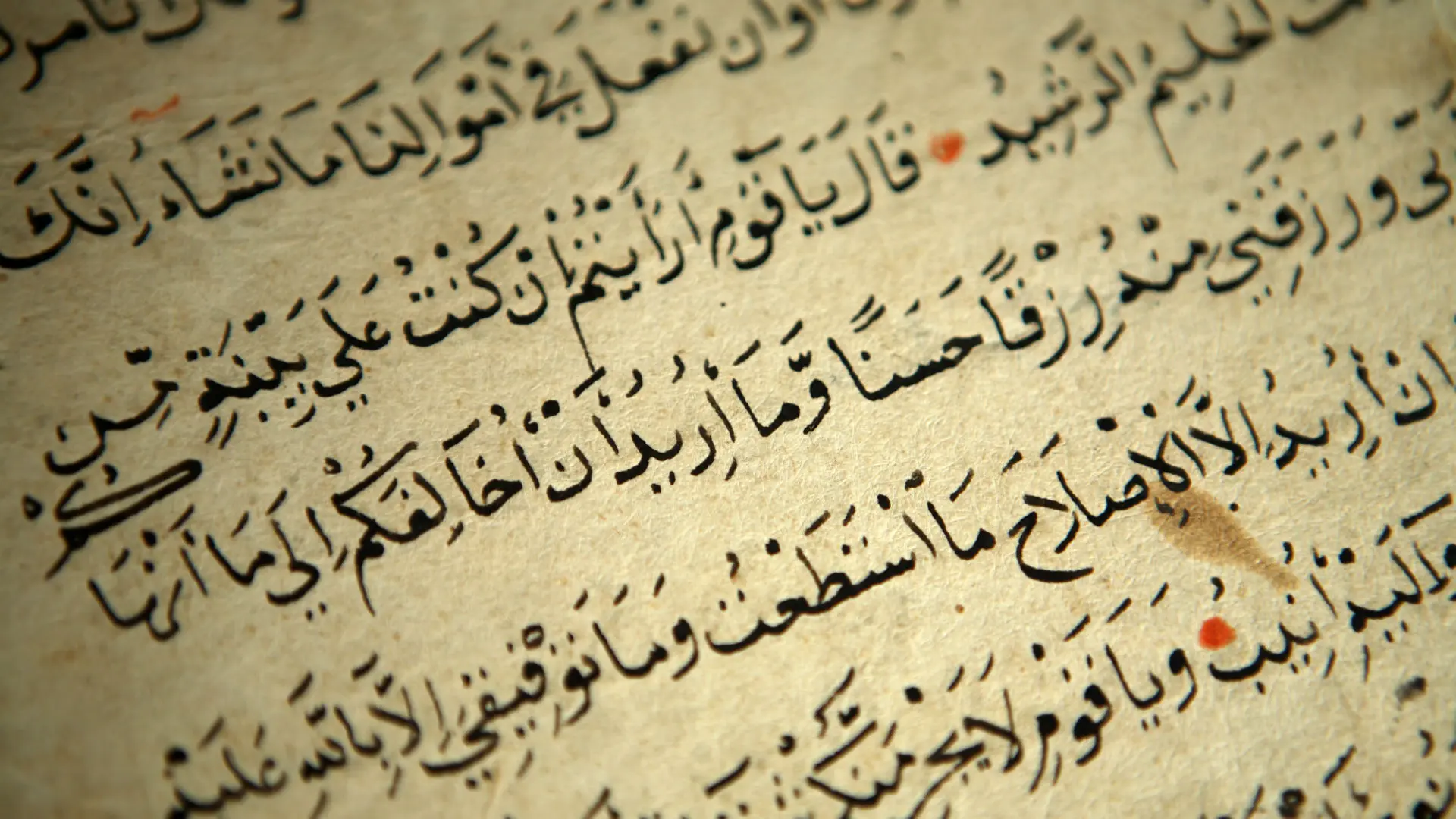

Early Arabic originated on the Arabian Peninsula as local spoken varieties of the Proto-Semitic language used commonly in the Fertile Crescent region dating back 5,000 years. As Arabic-speaking nomadic Bedouin tribes interacted through trade and conflict, Arabic continued developing into distinct but mutually intelligible dialects. The harsh desert environment of the peninsula necessitated concise yet descriptive words to effectively communicate about essential matters like water wells, vegetation, tribal disputes, camel grazing, and celestial bodies used for navigation, expanding the lexical richness of Arabic. As a predominantly oral language, early Arabic was spread through poets and storytellers, passing down cultural history and wisdom through epic poems, fables and songs. The Arabic script evolved from the Nabataean variation of Aramaic writing which added dots, strokes and curves enabling 28 consonants to be distinguished more easily.

Spread Through Islam and Islamic Golden Age

In the 7th century CE, the emergence of Islam led to Arabic expanding swiftly as the sacred language of the Quran and hadiths documenting Prophet Muhammed’s teachings. As Muslim rule unified Arabia then spread through conquest across North Africa, Spain and Persia over the next centuries, Arabic became the administrative language facilitating communication between the diverse ethnic groups in the Islamic empire. Arabic’s ascendance coincided with the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to 13th centuries when Muslim caliphates promoted knowledge, innovation and culture, establishing libraries, universities and patronizing scholars who produced groundbreaking work drawing on ancient Greek, Indian and Persian intellectual traditions. This was all conducted and compiled overwhelmingly in the Arabic language which became the international medium for discourse not just on theology but also philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, literature and more.

Variation and Standardization

As Arabic usage spread rapidly to non-native speakers from Morocco to Persia, considerable dialectal variations began emerging influenced by regional vernaculars. At the same time, Classical Arabic retained its status as the common standard in writing and formal speech due to its use in Islamic discourse. Various caliphates initiated attempts to systematize Classical Arabic’s grammar and pronunciation to prevent deviation from the pure speech of the Quran. This led to the development by the 8th century of Early Modern Arabic which endured for six centuries as the language of literature, history and science. In the 19th century, prosperous Arab nationalist movements sparked fresh interest in reviving Arabic as a unifying political and cultural identity. Building on centuries of stabilizing written Arabic, Early Modern Arabic vocabulary and grammar were reformed into Modern Standard Arabic in the 20th century for use in modern media and education across all Arabic-speaking countries while regional colloquial dialects continued evolving.

Arabic Language in Recent Centuries

From Europe’s Renaissance in the 15th century onwards, Arabic culture entered a prolonged stagnation as its great cosmopolitan cities and centers of scholarship declined amidst political fragmentation, economic disruption from new trade routes and the rise of Turkish and Persian empires. Interest and patronage in Arabic literary creation, philosophic inquiry and scientific research drastically receded. But as European colonialism expanded in the 19th century, a rediscovery and reclaiming of Arabic’s illustrious history and legacy was used to galvanize nationalist and modernist movements seeking self-determination and cultural identity for Arab societies. But despite Arabic retaining great symbolic value, increased mobility, communication and globalization in the 20th century has elevated English and even French as dominant languages in academia, international business and technology across the Middle East and North Africa. Mass media, computes and smartphones have also popularized informal Arabic registers, slangs and dialects more than the formal MSA taught in schools. Preserving and revitalizing Arabic continues to pose linguistic and cultural challenges in the 21st century global information age dominated by English.

Conclusion

Arabic history can be seen in four broad stages – its pre-Islamic origins amongst nomadic tribes and traders on the Arabian peninsula, the spread and enrichment of Arabic language and culture during the Islamic Golden Age, efforts to balance variations through standardization alongside continuously evolving colloquial dialects, and its revived symbolic but diminished practical role globally in modern times. Arabic was instrumental as the medium that facilitated the growth of Islamic civilization at its peak and its legacy remains a crucial pillar of identity and heritage for over 400 million Arabs worldwide today. But faced with the pervasive soft power and utilitarian advantages English provides in an interconnected post-colonial world, both Classical and Modern Standard Arabic will need active cultivation through education, media and public initiatives to maintain their functional relevance and prevent Arabic diglossia splitting permanently between formal and informal varieties.

Leave a Reply